User experience experts and web developers have a tough course; not only do they have to work together to create an aesthetically pleasing, functional site, they also have to dig deep into user psychologies to develop experiences that leave a lasting—and positive—impression of the brand. It requires both careful precision and a bit of guesswork, but the recent emergence and development of data trends is making the process more accessible.

Unfortunately, there are also some downsides and risks associated with this reliance on data.

The Wonders of Modern Data

Before we get too far ahead of ourselves, let’s be honest, the world of modern data is great. Thanks to big data and increasingly complex data visualization systems, we have access to more user data and insights than we ever have before. We can draw more objective conclusions, test our hypotheses, and generally strive for bigger and better results—but it’s also possible to depend too heavily on the conclusions we reach with these data sets.

The Pitfalls of Overreliance

Take a look at these reasons why overreliance on data is such a bad thing:

- Objective data isn’t always objective. Despite the advancement and sophistication of modern data-fetching tools (and research processes), we’re still not perfect at collecting user data. We’ll draw in incorrect information, neglect some other forms of information, or organize information in a misleading or imperfect way. As such, our data sets start off vulnerable to flaws. As a simple example, the Monder Law Group reminds us that “objective scientific data” isn’t objective when a test has been performed incorrectly, or when an outside force has interfered with results. The same can happen in the world of online data—all it takes is one hiccup to corrupt an entire batch of data.

- Data can stifle creative thought. When you rely too heavily on data sets to inform your conclusions, ideas, and strategies, you start limiting your creative potential. Instead of developing dynamic new tactics or coming up with ingenious tangential ways to beat the competition, you’ll turn into a call-and-response style designer, only jumping when the data says you should. This will stifle your creativity, and force you to think “inside the box.”

- It’s easy to misinterpret data. With data visualization in the mix, it’s easy to misinterpret data. You might look at a handful of spikes in a certain user action and believe it to be correlated with a specific design change, but the reality is, those spikes may be outliers tied to another variable. If you’re using these data fluctuations as a learning tool, forcing you to more closely evaluate your design and performance, you can walk away with meaningful conclusions, but if you base all your assumptions on these conclusions, you could end up going down the wrong path.

- Data interpretation requires subjective human questions. Remember, no matter how objective or informative your data sets could be, they’re still limited by the questions you ask of that data—and all human questions are biased and subjective in nature. Your questions dictate which pieces of data you examine, as well as the light in which you examine them. You may also come in with preconceived notions or assumptions about how the data will turn out, giving you a bias that may influence your overall conclusions. You can spin data almost any way you want, so taking it as objective truth can be dangerous.

- Human behavior is still unpredictable. Our current limitations of psychological understanding preclude us from fully predicting user behavior and user experiences, especially in bigger scales. No matter how much data you gather, or how closely you scrutinize it, you’ll never be able to predict user behavior universally or accurately. Using data as your sole basis for design decisions will lead you down a path with mixed results—and sometimes your gut instinct can serve you better.

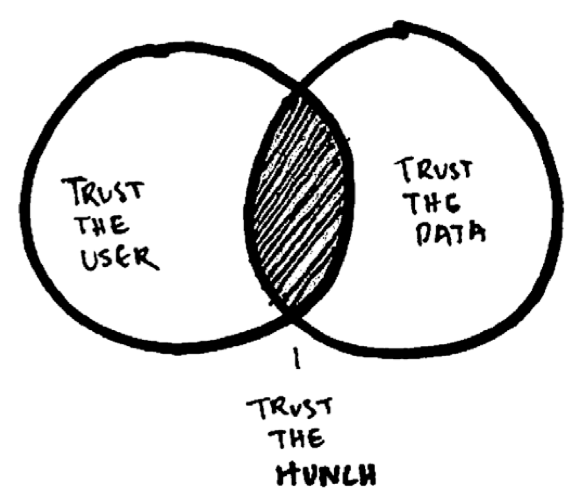

The problem here isn’t the utility of data, or using data as a tool; it’s sheer overreliance on data. Don’t use it as a crutch—instead, use it as a tool, and make a conscious effort to remove yourself and keep yourself as objective as possible. It isn’t easy to do, especially when the temptation is to generalize or form snap judgments, but it’s necessary if you want to preserve your creative potential and create the best possible end product for your users.